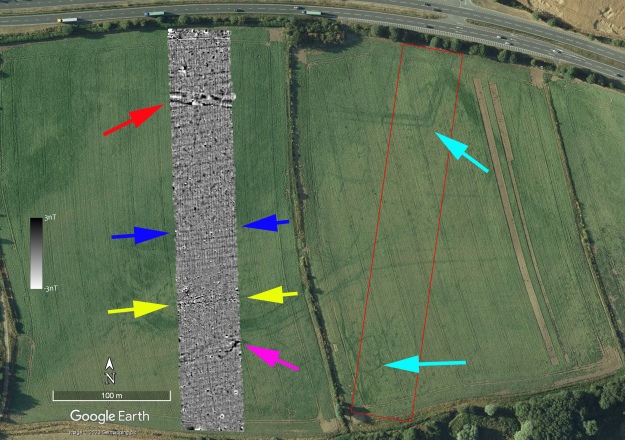

Regular readers of this blog will know that over the years we have surveyed both within and outside the walls of the Roman “small town” of Durobrivae near Peterborough. Before Christmas we completed the Boat Field just outside the SE gate of the town. Historic England asked if we could survey some transects across three fields south of the A1, just to the west of the town. Figure 1 shows the areas we have surveyed with magnetometry survey.

The sample survey transects are across three fields: Cherry Holt, The Glebe and Glebe Sands (Fig. 2).

The weather was not very pleasant. There was a cold wind blowing in from the east with squalls of rain to add to the delight (Figure 3). We did, however, manage to complete the three transects with time to spare. We completed 4.28ha of mag survey in the two days and had time to take magnetic susceptibility readings over the three transects in the afternoon of the second day. We swapped who was pushing the mag every 30m or so just so that the people holding the poles could warm up!

The first field we surveyed was Cherry Holt to the west. We completed a 340m x 50m long transect across the field by mid-afternoon. We chose the line of the transect in the hopes of detecting the double-ditched feature that can been seen in the Google Earth image, and has been seen in various Historic England air photos (Fig. 4, norrthern light blue arrow).

The first thing to notice in the magnetometry results are the east-west stripes and the north-south striations. The east-west stripes (the dark blue arrows indicate just one) are land drains. They show very clearly in the Glebe. The north-south striations are cultivation marks probably from when the field was last ploughed. The most obvious archaeological features are the double ditches indicated by the red arrow. I’ll discuss these in relation to the next transect.

The line of rather ferrous looking responses indicated by the yellow arrows look like an old fence line. To check this I downloaded the 19th century OS maps from Edina. After various failed attempts to get Google Earth into QGIS or the map data into Google Earth, I resorted to quickly digitizing the key features in QGIS and then importing those into Google Earth. Figure 5 shows the result. The red lines are the field boundaries and as you can see, one lines up perfectly with the feature in the mag data (Fig. 6). Hurrah! I have also plotted the “Roman house”, “Roman villa” and “iron works” from the OS map (Fig. 5).

The rather strange shaped feature in the southern half of the transect (Fig. 4, pink arrow, Fig. 6 red arrow) is hard to interpret. Due to its odd shape I’m guessing it is likely to be natural, but that is just a guess. The blue arrows in Figure 6 show the line of two linear features, maybe early field boundaries? They do not occur on the OS map so are earlier than the first surveys in the 19th century.

One entertaining observation regards the footpath shown in Figure 5. On the northern edge of Cherry Holt is a kissing gate with a bridge across the drainage ditch which runs alongside the A1. Judging by the brambles on the little footbridge I doubt anyone has used it in a while. Besides, one would have to be mad to try and cross the A1 on foot at this point (Fig. 7)!

In Figure 6 I have indicated three linear features with yellow arrows. We had originally thought these might be roadside ditches, but they do not show up at all in the mag data. The survey in the Glebe to the west suggests that at least some of them have a more prosaic origin.

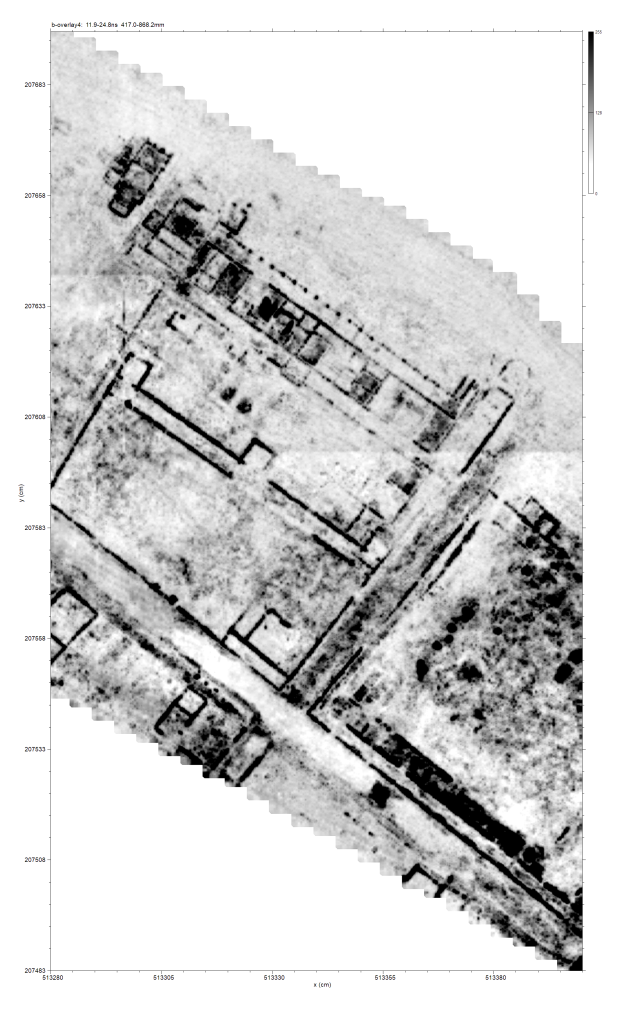

The aerial images of The Glebe (Fig. 4) show lots of features including the corner of the double-ditched feature and an enclosure towards the south. We placed the transect (Fig. 4, red line) to catch these features. Figure 8 shows the results.

The red arrows show the corner of the double-ditched enclosure. This feature was partially excavated when the A1 was widened. Stephen Upex is currently working on this legacy excavation and states that it contains Flavian pottery. The enclosure looks rather military even though it doesn’t have the classic “playing card” corner shape.

The field is covered in field drains. The yellow arrows show just one of them. The pink arrows indicate the southerly drain at which point the others run at right angles to it. This land drain lines-up with one of the linears shown with a yellow arrow in Figure 6. This suggests that our “road” might be connected to the drainage instead.

The blue and orange arrows indicate two further complexes of ditches. We have only just clipped the one indicated by the blue arrow but the crop marks suggest there is more to the west. The southern one matches the clear crop marks seen in the Google Earth image (southern light blue arrow in Fig. 4). Although this is near the “Roman villa” marked on the early OS maps, my gut feeling is that this is earlier, possibly late Iron Age. The straight ditch marked by the green arrow might be a boundary ditch for the villa if it lies slightly to the east of our transect.

From our survey and the aerial images, this field appears to be very busy archaeologically!

The final field to the east was Glebe Sands (Fig. 9). The transect went up a slope and then at the north end was a plateau. This can be seen clearly in the lidar image (Figure 10).

The flatter plateau marks the edge of the sands and gravels with alluvium downslope to the south. There are quarry pits along the edge of the plateau which is possibly the origin of the fieldname: Glebe Sands. The “iron working sites” marked on the 19th century OS map also lie on the plateau edge. The rather amorphous magnetic features are probably the remains of these quarry pits (Fig. 9). At the southern edge of our transect are some faint traces of field drains running NNW to SSE, one of which is indicated with the white arrow.

The northern end of our transect is very busy with a series of linear features, almost certainly ditches, and two circular features, one 10m in diameter and one 22m in diameter. These may be barrows, but it is curious they are cutting one another. Perhaps one is prehistoric and the other Roman or Saxon? Whatever the precise dating of these features it is clear that the gravel terrace attracted substantial multiperiod settlement.

Now that we have our own magnetic susceptibility meter, I am starting to collect some data at any site where we undertake a magnetometry survey. Over time I’m looking to build-up a database of readings compared to geology and our results. Ruth, Jim and I spent the last part of the afternoon collecting readings at roughly 25m intervals. In Figure 11 I have represented the results as shaded circles as the spacing seems too big to interpolate a continuous surface.

The results show some interesting contrasts. Cherry Holt has a more even pattern than the two other fields, and generally low readings. Geologically, according to the British Geological Society’s viewer, the field is split between river gravel terraces 1 and 2. The eagle-eyed of you would have noticed that the plot in Figure 4 is cropped to +/- 3nT whereas the Glebe and Glebe Sands images are cropped to +/- 4nT. Apart from the Roman double ditches at the north end, the features are relatively faint. In The Glebe, the readings at the north end of the field where the corner of the Roman ditches can be seen is high as would be expected where there is dense human occupation. The readings drop, however, as one gets closer to the south and the alluvium. The enclosure to the south of the transect does not show as a particularly high area of readings. In Glebe Sands, the southern area on the alluvium is very low, with the highest readings of all on the river terrace where all the activity is and the “iron workings”.

We have, therefore, two processes at work. The soils which develop on the alluvium have a lower magnetic susceptibility to those which develop on the river terraces, especially terrace 1. The magnetic susceptibility readings are then enhanced by anthropogenic factors where there is evidence of occupation.

Just to finish off, Figure 12 shows Jim with our new Sensys which conveniently has slots for carrying the target poles across the field.